Wine (software)

|

|

|---|---|

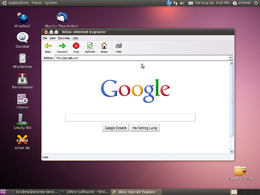

Screenshot of a built-in variation of Internet Explorer made for Wine running on Ubuntu. |

|

| Original author(s) | Alexandre Julliard |

| Developer(s) | Wine authors (1,249) |

| Initial release | 4 July 1993 |

| Development status | Active |

| Written in | C |

| Operating system | Unix-like systems |

| Platform | Cross-platform |

| Size | 15 MB (compressed) |

| Type | Compatibility layer |

| License | GNU LGPL v2.1+ |

| Website | www.winehq.org |

Wine is a free software application that aims to allow computer programs written for Microsoft Windows to run on Unix-like operating systems. Wine also provides a software library, known as Winelib, against which developers can compile Windows applications to help port them to Unix-like systems.[1]

Wine is not a full emulator, but is instead a compatibility layer, providing alternative implementations of the DLLs that Windows programs call, and a process to substitute for the Windows NT kernel. Wine is predominantly written using Black-box testing reverse-engineering, to avoid copyright issues.[2]

The project lead is Alexandre Julliard.

Contents |

Name

The name Wine initially was an acronym for WINdows Emulator[3]. Later on it was derived from the recursive acronym Wine Is Not an Emulator[4]. While the name sometimes appears in the forms WINE and wine, the project developers have agreed to standardize on the form Wine.[5]

History

Bob Amstadt (the initial project leader) and Eric Youngdale started the Wine project in 1993 as a way to run Windows applications on Linux. It was inspired by two Sun Microsystems' products, the Wabi for the Solaris operating system, and the Public Windows Initiative[6] (an attempt to get Windows API fully reimplemented in the public domain as an ISO standard, but rejected by the entity due to pressure from Microsoft in 1996).[7] Wine originally targeted Windows 3.x (16-bit) application software, although it now[update] focuses on 32-bit and 64-bit applications. The project originated in discussions on Usenet in comp.os.linux in June 1993.[8] Alexandre Julliard has led the project since 1994.

The project has proved time-consuming and difficult for the developers, mostly because of incomplete and incorrect documentation of the Windows API. While Microsoft extensively documents most Win32 functions, some areas such as file formats and protocols have no official Microsoft specification. There are also undocumented low-level functions and obscure bugs that Wine must duplicate precisely in order to allow some applications to work properly. Consequently, the Wine team has reverse-engineered many function calls and file formats in such areas as thunking.[9] More recently some developers have suggested enhanced tactics such as examining the sources of extant open-source and free software.

The Wine project originally released Wine under the same MIT License as the X Window System, but owing to concern about proprietary versions of Wine not contributing their changes back to the core project,[10] work as of March 2002 has used the LGPL for its licensing.[11]

Wine officially entered beta with version 0.9 on October 25, 2005.[12] Version 1.0 was released on June 17, 2008,[13] after 14 years of development. Version 1.2 was released on July 16, 2010.[14] Development versions are released roughly every two weeks.

Architecture

Wine implements the Windows API entirely in user space, rather than as a kernel module. Services normally provided by the kernel in Windows are provided by a daemon known as the wineserver. The wineserver implements basic Windows functionality, as well as integration with the X Window System, and translation of signals into native Windows exceptions.

Although Wine implements some aspects of the Windows kernel, it is not possible to use native Windows drivers with it, due to Wine's underlying architecture. This prevents certain applications from working, such as some copy-protected titles.

Portability

Wine is primarily developed for Linux, but the Mac OS X, FreeBSD and Solaris ports are currently well-maintained.[15] Wine is also available for OpenBSD and NetBSD through OpenBSD Ports[16] and NetBSD pkgsrc respectively. Outdated versions of Wine's DLLs are available for Microsoft Windows,[17] but Wine does not fully compile or run on Windows yet.[18]

Corporate sponsorship

The main corporate sponsor of Wine is CodeWeavers, which employs Julliard and many other Wine developers to work on Wine and on CrossOver, CodeWeavers' supported version of Wine. Crossover includes some application-specific tweaks not considered suitable for the WineHQ version, as well as some additional proprietary components.

The involvement of Corel for a time assisted the project, chiefly by employing Julliard and others to work on it. Corel had an interest in porting WordPerfect Office, its office suite, to Linux (especially Corel Linux). Corel later cancelled all Linux-related projects after Microsoft made major investments in Corel, stopping their Wine effort.[19]

Other corporate sponsors include Google, which hired CodeWeavers to fix Wine so Picasa ran well enough to be ported directly to Linux using the same binary as on Windows; Google later paid for improvements to Wine's support for Adobe Photoshop CS2. Wine is also a regular beneficiary of Google's Summer of Code program.[20][21]

Functionality

Software that runs flawlessly ("Platinum") Software that runs flawlessly with configuration ("Gold") Software with minor Issues ("Silver") Software with major Issues ("Bronze") Unusable software ("Garbage")

As of 2009[update], Wine runs some software packages with good stability and many others with minor issues.[22] The developers of the Direct3D portions of Wine have continued to implement new features such as pixel shaders to increase game support.[23] Wine can also use native DLLs directly, thus increasing functionality, but then a license for Windows is needed unless the DLLs were distributed with the application itself.

winecfg is a GUI configuration utility included with Wine. Winecfg makes configuring Wine easier by making it unnecessary to edit the registry directly, although, if needed, this can be done with the included registry editor (similar to Windows regedit). Wine also includes its own open-source implementations of several other Windows programs, such as notepad, wordpad, control, iexplore and explorer.

AppDB is a community-maintained database of which Windows applications work, and how well they work, with Wine.

Console applications

Wine partially supports Windows console applications, and the user can choose which backend to use to manage the console (choices include[24] raw streams, curses, and user32). Some applications (such as Whittaker's Words) actually run faster with more functionality in Wine than on native Windows. When using the raw streams or curses backends, Windows applications will run in a Unix terminal.

64-bit applications

Preliminary support for 64-bit Windows applications was added to Wine 1.1.10, in December 2008.[25] This currently requires at least gcc version 4.4, and the Wine developers expect that it will take significant time before support stabilizes. However, as almost all Windows applications are currently[update] available in 32-bit versions, and the 32-bit version of Wine can run on 64-bit platforms, this is seen as a non-issue.

The 64-bit port of Wine also has preliminary WoW64 support (as of April 2010[update]), which allows both 32-bit and 64-bit Windows applications to run inside the same Wine instance.[26]

Wine can run 16-bit Windows programs on an x86-64 (64-bit) CPU (sometimes referred to as AMD64). 64-bit versions of Microsoft Windows will not run 16-bit Windows programs.[27]

Usage

In a 2007 survey by desktoplinux.com of 38,500 Linux desktop users, 31.5% of respondents reported using Wine to run Windows applications.[28] This plurality was larger than all x86 virtualization programs combined, as well as larger than the 27.9% who reported not running Windows applications.[29]

Third-party applications

Some applications require more tweaking than simply installing the application in order to work properly, such as manually configuring Wine to use certain Windows DLLs. The Wine project does not integrate such workarounds into the Wine codebase, instead preferring to focus solely on improving Wine's implementation of the Windows API. While this approach focuses Wine development on long-term compatibility, it makes it difficult for users to run applications that require workarounds. Consequently, many third party applications have been created to ease the use of those applications that don't work out of the box within Wine itself. The Wine wiki maintains a page of current and obsolete third party applications.[30]

- CrossOver, proprietary software

- Bordeaux is a Wine GUI configuration manager that runs winelib applications. It also supports installation of third party utilities, installation of applications and games, and the ability to use custom configurations. Bordeaux currently runs on Linux, FreeBSD, PC-BSD, Solaris, OpenSolaris, and Mac OS X computers.

- Winetricks is a small script to install some basic components (typically Microsoft DLLs and fonts) required for some applications to run correctly under Wine. The Wine project will accept bug reports for users of Winetricks, unlike most third-party applications. It is maintained by Wine developer Dan Kegel.[31]

- Wine-Doors is an application-management tool for the GNOME desktop which adds functionality to Wine. Wine-Doors is an alternative to WineTools which aims to improve upon WineTools' features and extend on the original idea with a more modern design approach.[32]

- IEs4Linux is a utility to install all versions of Internet Explorer, including versions 4 to 6 and version 7 (in beta).[33]

- PlayOnLinux is an application to ease the installation of Windows applications (primarily games) using Wine. It uses an online database of scripts to apply to different applications that need special configuration; if the game is not in the database, a manual installation can be performed. Aside from games, any other program can be installed and each one is put in a different container (WINEPREFIX) to prevent interference of one program with another. This provides isolation in much the same way that CrossOver's bottles work. PlayOnLinux allows to install most favorable applications in Windows world, such as Apple iTunes and Safari, Microsoft Office, Microsoft Internet Explorer v. 6/7, AutoCAD, Mono, .NET Framework 2.0, Fireworks MX, Flash MX, and many others.[34]

Other versions of Wine

The core Wine development aims at a correct implementation of the Windows API as a whole and has sometimes lagged in some areas of compatibility with certain applications. Direct3D, for example, remained unimplemented until 1998,[35] although newer releases have had an increasingly complete implementation.[36]

CodeWeavers markets CrossOver specifically for running Microsoft Office and other major Windows applications including some games. CodeWeavers employs Alexandre Julliard to work on Wine and contributes most of its code to the Wine project under the LGPL. CodeWeavers also released a new version called Crossover Mac for Intel-based Apple Macintosh computers on January 10, 2007.[37]

CodeWeavers has also recently released CrossOver Games, which is optimized for running Windows computer games. Unlike CrossOver, it doesn't focus on providing the most stable version of Wine. Instead, experimental features are provided to support newer games.[38]

TransGaming Technologies produces the proprietary Cedega software. Formerly known as WineX, Cedega represents a fork from the last MIT-licensed version of Wine in 2002. Much like Crossover Games, TransGaming's Cedega is targeted towards running Windows computer games and is sold using a subscription business model.

TransGaming has also produced Cider, a library for Apple–Intel architecture Macintoshes. Instead of being an end-user product, Cider (like Winelib) is a wrapper allowing developers to adapt their games to run natively on Intel Mac OS X without any changes in source code.

Russian company Etersoft has been developing a proprietary version of Wine since 2006. WINE@Etersoft supports popular Russian applications for business, accounting, trade etc. (for example, 1C:Enterprise by 1C Company).[39] In 2010, Etersoft is going to issue WINE@Etersoft CAD which is oriented towards CAD systems such as AutoCAD, Bricscad and Compass-3D (a popular Russian CAD-system).

Other projects using Wine source code include:

- ReactOS, a project to write an operating system compatible with Windows NT down to the device driver level. ReactOS uses Wine source code considerably, but because of architectural differences, ReactOS code (such as dlls written specifically for it, e.g. ntdll, user32, kernel32, gdi32, and advapi) is not generally reused in Wine.[40] In July 2009, Alex Bragin, the ReactOS project lead, started[41] a new ReactOS branch called Arwinss,[42] and it was officially announced in January 2010.[43] Arwinss is an alternative implementation of the core Win32 components, and uses mostly unchanged versions of Wine's user32.dll and gdi32.dll.

- Linux Unified Kernel, a project intended to be binary-compatible with application software and device drivers made for Microsoft Windows and Linux. This kernel imports all the key features of the Windows operating system kernel into the Linux kernel to support both Linux and Windows applications and device drivers.

- Darwine, a port of the Wine libraries to Darwin and Mac OS X. Darwine originally aimed at compiling Windows source code to Mach-O binaries. With the advent of Apple–Intel architecture, Darwine began running Win32 binaries in x86 Darwin and has approached version parity with the Wine trunk. The Darwine project also continues progress on PowerPC by combining Wine with the QEMU x86 emulator.

- Odin, a project to run Win32 binaries on OS/2 or convert them to OS/2 native format. The project also provides the Odin32 API to compile Win32 programs for OS/2.

- E/OS, a project attempting to allow any program designed for any operating system to be run without the need to actually install any other operating system.

- Rewind, a defunct MIT-licensed fork of the last MIT-licensed version of Wine.

- Parallels Desktop 3 for Mac, a proprietary product that uses some Wine code for its DirectX handling.

- VirtualBox v3.x, an Open-Source product that uses some Wine code for its Direct3D handling.

Microsoft and Wine

Microsoft has generally not made public statements about Wine. However, the Microsoft Update software will block updates to Microsoft applications running in Wine. On February 16, 2005, Ivan Leo Puoti discovered that Microsoft had started checking the Windows registry for the Wine configuration key and would block the Windows Update for any component. Puoti wrote, "It's ... the first time Microsoft has acknowledged the existence of Wine."[44]

The Windows Genuine Advantage (WGA) system also checks for existence of Wine registry keys. The WGA FAQ states that WGA will not run in Wine by design, as Wine does not constitute "genuine Windows".[45] When WGA validation detects Wine running on the system, it will notify users that they are running non-genuine Windows and disallow genuine Windows downloads for that system. Despite this, some reports have circulated of the WGA system working in Wine,[46][47] although this loophole has now been closed with the next WGA component update. In the case of Internet Explorer 7 and Windows Media Player, Microsoft has since removed the WGA requirements.

Security

Because of Wine's ability to run Windows binary code, concerns have been raised over native Windows viruses and malware affecting Unix-like operating systems.[48] Wine can run much malware, but programs running in Wine are confined to the current user's privileges, restricting some undesirable consequences. This is one reason Wine should never be run as the superuser.[49] Malware research software such as ZeroWine[50] runs Wine on Linux in a virtual machine, to keep the malware completely isolated from the host system.

Wine vs. native Unix applications

A common concern about Wine is that its existence means that vendors are less likely to write native Linux, Mac OS X and BSD applications. As an example of this, consider IBM's 1994 operating system, OS/2 Warp. An article[51] describes the weaknesses of OS/2 which killed it, the first one being:

| “ | OS/2 offered excellent compatibility with DOS and Windows 3.1 applications. No, this is not an error. Many application vendors argued that by developing a DOS or Windows app, they would reach the OS/2 market in addition to DOS/Windows markets and they didn't develop native OS/2 applications. | ” |

See also

- ReactOS, an open-source operating system which is a clone of Microsoft Windows and uses some libraries from Wine.

- System call

- Executor (discontinued project, although now open source), like Wine, except that it attempts to run Macintosh software on other operating systems, translating Macintosh Toolbox API calls and QuickDraw routines into equivalent Win32 or POSIX API calls.

- Windows Interface Source Environment

- LBW: Linux Binaries on Windows requires Interix to be installed first.

References

- ↑ "Winelib". Wine HQ. http://winehq.org/site/winelib. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ↑ Legal Issues, By James Mckenzie, Posted: Sat Dec 26, 2009 8:50 pm, Forums, WineHQ

- ↑ WINE FAQ Old meaning of the name even used until 1997

- ↑ Wine Is Not an Emulator First proposal to change the meaning of the name WINE

- ↑ "Why do some people write WINE and not Wine?". Wine Wiki FAQ. Official Wine Wiki. 2008-07-07. http://wiki.winehq.org/FAQ?action=recall&rev=217#head-8b4fbbe473bd0d51d936bcf298f5b7f0e8d25f2e. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ Bob Amstadt (1993-09-29). "Wine project status". comp.windows.x.i386unix. (Web link). Retrieved on 2008-07-13.

- ↑ "Sun Uses ECMA as Path to ISO Java Standardization". Computergram International. 1999-05-07. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0CGN/is_1999_May_7/ai_54580586. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ Byron A Jeff (25 August 1993). "WABI available on linux or not". comp.os.linux.misc. (Web link). Retrieved on 2007-09-21.

- ↑ Loli-Queru, Eugenia. Interview. Interview with WINE's Alexandre Julliard. 2001-10-29. Retrieved on 2008-06-30. "Usually we start from whatever documentation is available, implement a first version of the function, and then as we find problems with applications that call this function we fix the behavior until it is what the application expects, which is usually quite far from what the documentation states."

- ↑ Jeremy White (2002-02-06). "Wine license change". http://www.winehq.org/pipermail/wine-devel/2002-February/003912.html. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ Alexandre Julliard (2002-02-18). "License change vote results". http://www.winehq.org/pipermail/wine-devel/2002-February/004487.html. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ http://www.winehq.org/news/2005102502

- ↑ "Announcement of version 1.0". Wine HQ. 2008-06-17. http://winehq.org/announce/1.0. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ↑ Release News, by Alexandre Julliard July 16, 2010

- ↑ "Under what hardware platform(s) and operating system(s) will Wine(Lib) run?". Wine FAQ. http://www.winehq.org/site/docs/wine-faq/index#UNDER-WHAT-PLATFORMS-WILL-WINE-RUN. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "OpenBSD Ports: emulators/wine". Openports.se. http://openports.se/emulators/wine. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "Wine Win32 Packages". sourceforge.net. http://sourceforge.net/project/showfiles.php?group_id=6241&package_id=112520. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "The Official Wine Wiki: Wine on Windows". Wiki.winehq.org. http://wiki.winehq.org/WineOnWindows. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (February 25, 2002). "That's All Folks: Corel Leaves Open Source Behind". Linux.com. http://www.linux.com/archive/feature/21411. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Kegel, Dan (2008-02-14). "Google's support for Wine in 2007". wine-devel mailing list. http://article.gmane.org/gmane.comp.emulators.wine.devel/56872. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Open Source Patches: Wine". Google. http://code.google.com/opensource/wine.html. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ↑ "Wine Application Database". WineHQ.org. http://appdb.winehq.org/. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "DirectX-Shaders". Official Wine Wiki. http://wiki.winehq.org/DirectX-Shaders. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Text mode programs (CUI: Console User Interface)". Wine User Guide. http://www.winehq.org/docs/wineusr-guide/cui-programs. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ↑ Lankhorst, Maarten (2008-12-05). "Wine64 hello world app runs!". wine-devel mailing list. http://www.winehq.org/pipermail/wine-devel/2008-December/070941.html. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- ↑ "Wine64 for packagers". Official Wine Wiki. http://wiki.winehq.org/Wine64ForPackagers. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ http://www.windowsitpro.com/article/performance/why-can-t-i-install-16-bit-programs-on-a-computer-running-the-64-bit-version-of-windows-xp-.aspx

- ↑ "2007 Desktop Linux Market survey". 2007-08-21. http://www.desktoplinux.com/cgi-bin/survey/survey.cgi?view=archive&id=0813200712407. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ↑ Running Windows applications on Linux, 2007 Desktop Linux Survey results revealed, By Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols, Aug. 22, 2007, DesktopLinux

- ↑ "Third Party Applications". Official Wine Wiki. http://wiki.winehq.org/ThirdPartyApplications. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "winetricks". Official Wine Wiki. http://wiki.winehq.org/winetricks. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Wine doors". Wine doors. http://www.wine-doors.org/. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "IEs4Linux". Tatanka.com.br. http://www.tatanka.com.br/. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "Play on Linux". Play on Linux. http://www.playonlinux.com/en. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ Vincent, Brian (2004-02-03). "WineConf 2004 Summary". Wine Weekly News (WineHQ.org) (208). http://www.winehq.com/?issue=208. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Wine Status - DirectX DLLs". WineHQ.org. http://www.winehq.org/status/directx. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "CodeWeavers Releases CrossOver 6 for Mac and Linux". Slashdot. http://linux.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid=07/01/10/1924235. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "Crossover Games site". Codeweavers.com. 1990-01-06. http://www.codeweavers.com/products/cxgames/. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "WINE@Etersoft - Russian proprietary fork of Wine (Russian)". Pcweek.ru. 2010-04-21. http://www.pcweek.ru/themes/detail.php?ID=72021&phrase_id=97643. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "Developer FAQ". ReactOS. http://www.reactos.org/en/dev_faq.html. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "Creation of Arwinss branch". Mail-archive.com. 2009-07-17. http://www.mail-archive.com/ros-diffs@reactos.org/msg01658.html. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "Arwinss at ReactOS wiki". Reactos.org. 2010-02-20. http://www.reactos.org/wiki/Arwinss. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ "Arwinss presentation". Reactos.org. http://www.reactos.org/archives/public/ros-dev/2010-January/012709.html. Retrieved 2010-04-27.

- ↑ Puoti, Ivan Leo (February 18, 2005). "Microsoft genuine downloads looking for Wine". wine-users mailing list. http://www.winehq.org/pipermail/wine-users/2005-February/016988.html. Retrieved 2006-01-23.

- ↑ "Genuine Windows FAQ". Microsoft Corporation. http://www.microsoft.com/genuine/downloads/FAQ.aspx. Retrieved 2006-01-30.

- ↑ "Ubuntu Linux Validates as Genuine Windows". Slashdot. http://linux.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid=07/06/18/0037223. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ "WGA running in Wine". http://forums.bit-tech.net/showthread.php?t=95654. Retrieved 2009-01-03.

- ↑ Matt Moen (2005-01-26). "Running Windows viruses with Wine". (Web link). Retrieved on 2009-10-23.

- ↑ "Should I run Wine as root?". Wine Wiki FAQ. Official Wine Wiki. 2009-08-07. http://wiki.winehq.org/FAQ?action=recall&rev=312#head-96bebfa287b4288974de0df23351f278b0d41014. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ↑ ZeroWine project home page

- ↑ Michal Necasek. "OS/2 Warp history". http://pages.prodigy.net/michaln/history/os2warp/index.html.

Further reading

- Jeremy White's Wine Answers - Slashdot interview with Jeremy White of CodeWeavers

- Jeremy White interview on the "Mad Penguin" web-site

- Appointment of the Software Freedom Law Center as legal counsel to represent the Wine project

- Wine: Where it came from, how to use it, where it's going - a work by Dan Kegel

External links

- Wine Development HQ - the official homepage of Wine

- Wine newsgroup (Google web interface)

- Wine at Freshmeat

- Wine (software) at Ohloh.net